As I said yesterday, I’m playing with flash writing. I struggle, because I love words. But that is probably because the writers I have been most informed and shaped by also loved words. I love a good story.

In other words, I need to read more writers who tell stories with economy.

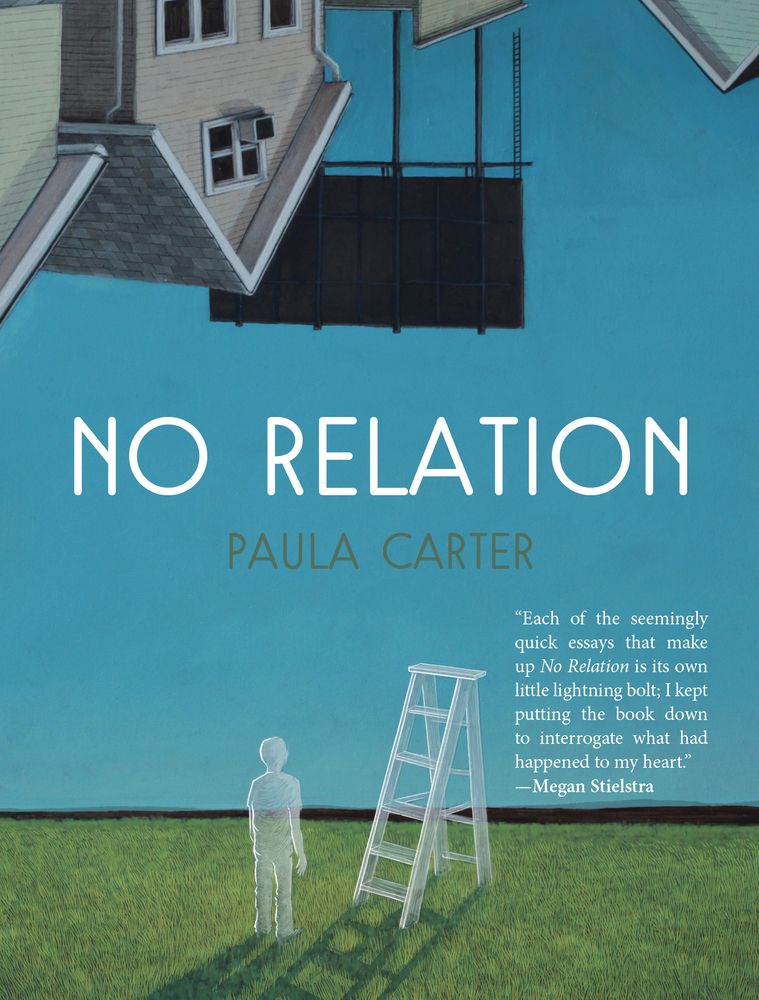

Several websites pointed me to the memoir No Relation, by Paula Carter (https://bookshop.org/p/books/no-relation-paula-carter/12167871). It’s 147 pages, and it’s a small format book – slightly smaller than a trade paperback. The synopsis, from the publisher:

When Paula first met James, she was 26, in graduate school, and not ready to be any kind of mother to his two young sons. But, years later, after caring for them and watching them grow, she finds herself unsure of what to do when her relationship with their father ends. In a collection of striking flash essays, Paula reveals the complexity of loving children who are not her own and attempts to put language to something we have no language to describe. No Relation is a deeply personal, beautifully rendered account of a seldom-remarked on kind of love and loss.

I did not expect to like this book, being someone who doesn’t generally read relationship memoirs, but it was a pleasant surprise. It turns out, I had a lot of resonance with the author, being someone who was once in love with someone who came with kids.

But the reason I bought the book is because while it’s a full memoir, it’s made up of ~85 very short (all under 250 words, I think) standalone flash essays, and I wanted to see how she did it.

It was well done, and it had that feeling like you are watching a magic trick, and you know you are watching a magic trick, but it doesn’t feel like a trick – it feels real. Put another way, the technique faded into the background, as it should.

Recommended both as a memoir, and as an example of the flash-essay-as-book technique.